A Path Forward for the African Space Agency

The inauguration of the African Space Agency (AfSA) on January 25, 2023 heralded a decades long push for a continental agency to direct space affairs within Africa. In this series, Kwaku Sumah examines the stated aims and goals of the agency, and asks, is it possible for the AfSA to achieve its stated aims as designed?

Read the previous Parts One, Two, Three, Four, Five, Six, and Seven

As the AfSA has already been formally inaugurated, designing the path forward must be built around principles that allows it to have the greatest impact on the continent. Any path forward requires the private sector to be prioritised, the scope of the AfSA to be reduced, and a decentralised model to be implemented to make the entire system more anti-fragile.

A new approach should also attempt to solve the other objections distilled previously, namely that (i) intra-African cooperation should be led by regional entities; (ii) Member States should cooperate on a non-dilutive basis accounting for their capabilities, expertise, funding, and space-readiness; and (iii) Member States should understand the value proposition and see direct and indirect benefits from their activities.

1.1 Decentralize and Develop Layered Systems

The fragility of a top down structure is generally a consequence of the fragility of its components. Thus, by separating the overall continental structure into different layers, each component is now capable of containing local disruptions. This improves the system’s ability to rebuff contagions from spreading through the entire system, as well as allows each layer and component to adapt by learning from other units in different layers. Similarly, this approach would help ease the continental language divide and associated cultural differences which must be considered when designing unions to ensure representation and integration.

For Africa this can be envisioned as a layered system wherein countries cooperate regionally to form supranational (bi- or multi-lateral) subsystems before finally coalescing to complete the larger continental system. The top-level continental system would be run by the AfSA, mainly to provide the centralised advantage of a clear and focused vision and direction to achieve the continental goals set out in the African Space Policy and Strategy.

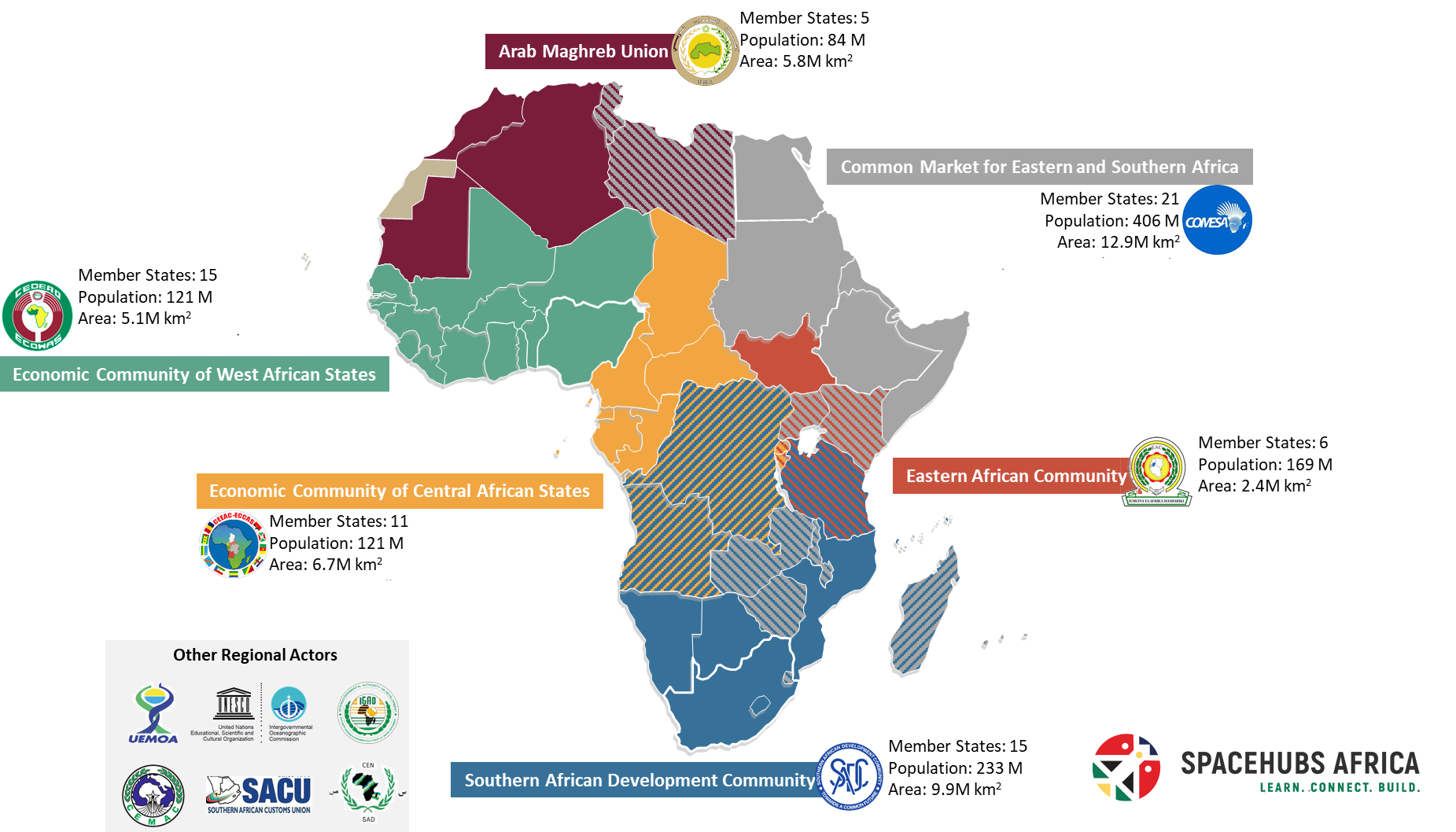

In terms of regional cooperation, Regional Economic Communities (RECs) were formed by African nations from the 1960s to 1990s, targeting economic cooperation and integration. Today there are several RECs to facilitate mutual economic development and trade. An overview of these can be seen in the following figure.

Regional Economic Communities operating on the African Continent

The assortment of all these regional blocs and subgroups highlight the embedded partnerships between African groups who are familiar on collaborating on a regional level to achieve various goals. The East African Community (EAC), Economic Community of Central African States (ECCAS), Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS) and Southern African Development Community (SADC) have also established customs unions which further sets the stage for regional cooperation and collaboration, also between private actors.

A cooperative-competitive dynamic can be established within the REC by the prominent space agencies. These agencies can jockey to lead and direct regional affairs by helping to identify and address pressing regional needs. In this framework, the larger space agencies would work through the RECs to define and pursue overarching regional goals alongside their own national ambitions. Regional cooperation through RECs would be especially useful to avoid creating new structures with different reporting lines, or pursuing capitally intensive cooperative mechanisms.

While Munsami and Nicolaides argued that such an approach could “cause a divergence in national and regional interests, especially when such foci are mutually exclusive or when cost becomes an overriding factor for implementation”,[1] regional cooperation in general largely follows the will of the most influential players. Additionally, given the low regard with which many African governments view space science and its applications, regional progress and direction needs to be provided by the most advanced regional players. In parallel, diverging national and regional interests is not necessarily a detriment, as shown by the Asian space dynamic.

On the supranational level, each state would still be able to independently form bi- or multi-lateral agreements to address gaps left by regional activities or to pursue their own goals. Collaboration can also be fostered independently between research institutes, universities, and space communities on the regional and supranational level, further promoting the transfer of knowledge, technology, and skills in neighbouring countries; as well as aiding in local and regional integration. This allows each entity to focus on their own strengths and leverage their neighbours’ capacities and strengths to cover their own weaknesses.

“One of the key lessons learned from the Asian case study is that, although there was a multiplicity of regional initiatives that fostered competition between the larger regional space superpowers, it was actually a boon for smaller nations who at least had some way of participating in the ecosystem, and could benefit from the different options on the table.”

This approach results in participating states’ receiving direct economic and social returns on the local level, through native space companies and institutions; on the national level, through national space policies; on the supranational level, as a result of bi- or multi-lateral cooperation; and on the regional level, through regional programmes and activities. Their needs and requirements are thereby addressed throughout the various levels. In addition, the states are able to use space as a vehicle to expand their local economic markets and to shape the future of the region.

Larger, more developed space nations are especially motivated by the ability to gain influence in their region, direct space affairs and requirements, and get easier access to export markets in their region. In contrast, less developed space nations benefit from their developed neighbours’ space systems being used in their regions, as well as from the freedom to direct their own affairs. They also benefit from access to the expanded markets of their neighbours, and by being able to use their funds directly in their own nations.

One of the key lessons learned from the Asian case study is that, although there was a multiplicity of regional initiatives that fostered competition between the larger regional space superpowers, it was actually a boon for smaller nations who at least had some way of participating in the ecosystem, and could benefit from the different options on the table.

Competition is a key driver for progress. With regional space powers competing for influence in their region to gain a larger share of regional markets, or the right to define regional needs, space actors in those regions are incentivised to work efficiently and effectively to develop local markets and adopt more effective measures. This could also catalyse local politicians and government bodies to pay more attention to space and create local regulatory environments that are conducive to growth.

Overall, the structure would consist of a:

Continental level: driven by the AfSA to ensure high-level cohesion and fulfilment of continental objectives.

Provide overall clarity regarding the path forward and help to steer efforts.

Direct funds for public goods, either through anchor tenancy or other means.

Coordinate foreign relations and represent African needs internationally.

Support expansion of African markets, space assets, services, and technology standards internationally as a tool for economic diplomacy.

Enable a regulatory environment conducive to commercial activities.

Communicate the benefits of space technologies to regional and national bodies, and strengthen research, development and innovation in space science and technology.

Regional level: driven by RECs, large space agencies, as well as regionally active institutions (e.g. RCMRD) to coalesce and aggregate regional needs and requirement.

Gather regional requirements, and engage Member States in space-related activities, education, training and research.

Direct funds for public goods, either through anchor tenancy or other means.

Promote regional integration between space institutions and companies, and open up regional markets for the export and import of space-derived products and services.

Communicate benefits of space technologies to local and regional bodies, and strengthen research, development and innovation in space science and technology.

Develop products and services using African capacities, and increase the African space asset base.

Execute and manage regional space programmes and initiatives.

Local level: driven by private actors, local governments, and space bodies, to serve local needs, build up capacity and an industrial base.

Develop capabilities, focusing on establishing national industrial base and policy, as well as space-specific expertise.

Create products and services using African capacities. Develop and increase the African space asset base. Leverage space assets to serve local needs.

Build synergies between civil and military stakeholders to accelerate innovation in dual-use sectors.

Provide an attractive business, tax, and regulatory environment that is flexible and pragmatic enough to respond to future changes in market structure.

Direct funds for public goods, either through anchor tenancy or other means.

Advocate for space to the general populace, and strengthen research, development and innovation in space science and technology.

The defined approach addresses concerns raised previously by leveraging relevant methods used in ESA and in Asia; promoting regional integration and intra-African cooperation without the need for involvement of a continental body; reducing the problems caused by a mismatch of partners of different capabilities, expertise, and experiences; helping to strength regional institutions; providing Member States with political, strategic, and economic incentives for participation, outside of just international cooperation; and ultimately providing better alignment with regional activities.

On top of all that, it rejects the legacy centralised model and puts private sector development first, ensuring the successful use of space technologies and assets for the development of Africa.

1.2 Ensure Everyone Has Skin-in-the-Game

This approach has the added benefit of ensuring that all actors have skin-in-the-game when it comes to the development of the African space ecosystem. Skin-in-the-game implies that one has incurred a certain level of risk and responsibility by involvement in the pursuit of a goal. An anti-fragile system ensures that all participants have skin-in-the-game and are accountable to the consequences of their actions. This accountability raises the personal motivation of each entity, who are thus likelier to avoid unwarranted risks and make better decisions for the whole.

In the current formulation of the AfSA, countries are expected to provide funding and support to a continental body, where the direct benefit to their own ecosystem is unclear. They yield their authority, agency, expertise, and skin-in-the-game to a body that is ostensibly working towards the benefit of the continent – which may come at the cost of their own country’s development. The majority of African countries are currently focused on growing their own local space ecosystem, and are at a very early stage of development – without a space policy, space agency, or even real space ambitions. In this structure, yielding their already scarce resources to a continental agency is hard to justify. Larger space countries in Africa also may question why they would provide resources, at the cost of their own programs, to a continental agency whose impact or ability to make effective use of those resources has not yet been established.

1.3 Role of the Private Sector

For individual space firms to be successful internationally, they need to adopt agile approaches, develop effective risk-mitigation and contingency plans, employ strong business models, and continuously innovate, while controlling cost and maintaining development and launch schedules. This is especially difficult, as space is also technically difficult. This highlights the need for talented employees, access-to-finance, and appropriate support mechanisms for private actors.

Given that the challenges are already great for space firms; it is essential for governments to construct an enabling environment, without needlessly restrictive policies increasing entry barriers. As explored in the various case studies, developing an effective NewSpace ecosystem requires governments to streamline the business and regulatory environment for firms, and provide new funding approaches that allows the private sector to take on more risk and innovate.

Anchor tenancy is a scheme commonly used by governments, and can be employed on the local, supranational, regional, and continental levels, helping to reduce risk and encourage private investment alongside public funding. It also allows governments and unions to direct the private sector towards the socioeconomic benefit of Africa as a whole. Governments and unions acting as customers for the private sector could also reduce the total amount of funding needed from Member States. This would occur as the governments/unions need not take on the burden of technological R&D, commercialisation, product iteration, staffing, nor deal with the other associated overhead of coordinating and controlling implementation.

Each layer may however pursue their own funding or procurement strategies, in case anchor tenancy is deemed not a good fit. In regions where the commercial market is too underdeveloped to employ an anchor tenancy approach, governments and unions could employ the common centrally-directed investment approach to bolster local infrastructure. On the other hand, in regions of strong commercial demand, private investment by itself could be sufficient.

Continental, regional, and local solutions could be tailored for near-to-market solutions, R&D, or commercial applications. The AfSA could even think to co-finance regional initiatives or operate a Fund-of-Funds (FoF) model to channel funds into a number of regional or local space-related funds. This enables a more flexible funding structure more responsive to changing local structure and market needs.

“The future of the African space ecosystem is dependent on Africa’s ability to develop and sustain private economic activity, and African unity.”

Given the existing economic integration through the RECs, the private sector would also benefit greatly through the furthering of intra-African trade and business, which would help to expand space export markets. An accommodating market structure would also entice foreign firms to try and enter the market, which, if appropriately regulated, could be a boon for the African market and boost technology transfer.

Similarly, reducing the barriers towards business and entrepreneurship would encourage local talent to stay within Africa, reducing brain drain and addressing the technical gap within Africa. Africans in the diaspora could also be encouraged to return to Africa to set up businesses using knowledge and skills gained abroad.

Regional collaboration by private actors already occurs in the realm of space science. The All Nations University College from Ghana is spearheading an African Constellation Satellite Network (AFCONSAT), with participation from Togo, Burkina Faso, Ivory Coast, Sierra Leone, Cape Verde, Guinea, Lesotho, and Botswana. Support from regional bodies could increase this effect also in the private sector. This collaboration also has the added effect of raising the level of space awareness within the region, and regional actors could work to advocate for space applications in their region. Cooperation need not require large financial commitment and would occur only on a need basis.

The future of the African space ecosystem is dependent on Africa’s ability to develop and sustain private economic activity, and African unity. Even outside of space, private economic activity has worked to tie together people whose states or governmental bodies are at odds. Within space, private actors represent the most important catalyst for the growth of the space industry.

Including local private space actors into the vision of Agenda 2063 The Africa We Want through anchor tenancy and public procurement, encourages them and aligns them to the continental vision by providing them with skin-in-the-game.

2 Conclusion

With greater participation from regional and local bodies, the role of the AfSA itself becomes more simplified and streamlined.

As mentioned earlier, public goods are typically underprovided if left exclusively to the market, so a key goal for the AfSA should be to ensure the provision of those goods. It can do so by:

Serving as a single access point to African markets and negotiating agreements with external agencies and organisations. This point was also mentioned by Martinez, who described how the AfSA could consider proposals from entities outside of Africa for space systems devised by the international industry to solve Africa’s needs.[2] Similarly, Aganaba-Jeanty spoke on how the AfSA could unify and safeguard the interests of Africa in areas such as the International Telecommunication Union for the allocation of orbital slots.

Acting as a space ambassador for the continent, helping to promote the adoption of space products and services, and raise awareness of the benefits of space programmes for Africa. In addition, as described by Martinez, helping to embed the African space community into Africa’s political structure and leadership.

Advocating for and developing streamlined governmental regulation and support, to create a continental regulatory environment that enables African commercial activities to thrive – with a focus on promoting NewSpace approaches and mechanisms.

Addressing funding gaps for scientific research, and acting as an anchor tenant for regional and local African space start-ups, consortia, and institutions; ultimately providing incentives to drive African development.

Supporting regional institutions in developing a critical mass of African capacities in space through education and training programmes.

Helping to coordinate regional and intra-Africa cooperation on space projects and regulating negative externalities such as space debris.

Exploring how to exploit existing space infrastructure in Africa as proposed by Gottschalk who noted several previously foreign-owned infrastructure including:

US-built runways and lighting for emergency shuttle landings in Gambia and Morocco;

Italian-built San Marco launch platform and Malindi telemetry facilities in Kenya;

OTB test range and NASA satellite dish in South Africa; and

Optical, radio and gamma-ray telescopes in Egypt, Mauritius, Namibia, and South Africa.

This approach provides nations and regional institutions greater agency and responsibility, and also means that a smaller initial financial commitment is needed by Member States, who are then expected to use their funds to develop their local and regional markets. In this structure, the AfSA would still be able to achieve the high-level policy goals of the African Space Policy and Strategy, while leaving the more specific objectives largely to regional, supranational and national bodies.

Although this split of responsibility, now shared between continental, regional, and local levels, could lead to a duplication of efforts, or redundancy within the overall system, as suggested by Munsami and Offiong in their analysis of Europe;[3] this is a key to developing an anti-fragile system that is able to respond to any form of stressor or disruption, and should therefore be embraced. Some measures could however be taken to make the opportunities more streamlined and accessible to end users.

Kwaku Sumah

Kwaku is the founder of Spacehubs Africa, and has been active in the space industry since 2016, working as a consultant for European and African space institutions and companies. He has worked on projects across the entire space value chain, including analysis on downstream markets, space debris evolution, planetary defence, and the launch market; as well as an assessment of the European financing landscape and due diligence on space companies.

[1] V. Munsami, A. Nicolaides, “Investigation of a governance framework for an African space programme”, Space

Policy, 2017, http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.spacepol.2016.08.003.

[2] Peter Martinez, “Is there a need for an African space agency?”, Space policy, vol. 28. Issue 3, August 2012, pp. 142-145.

[3] V. Munsami, E.O. Offiong, “Should Africa follow the European space governance model for an African space

programme?”, Space Policy, 2017, http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.spacepol.2017.03.005.